Language Modeling - Letting the AI Speak for Itself

Image courtesy of wjct.org

This blog post covers the growing use of language modeling for natural language generation, particularly with deep learning models, and recent research in applying this to create narratives and stories.

This post assumes that the reader has some background knowledge in the area of language modeling and deep learning. For those who do not, or those who would like a quick review, we have also written this handy blog post describing knowledge and concepts that will help get you up to speed with prominent methods and models in this area.

For an in-depth overview of developments in natural language generation prior to the current deep learning era, we highly recommend this survey of the area (Gatt and Krahmer, 2018).

Table of Contents

- Language Modeling and Generation with Deep Learning

- Evaluating Language Models

- Applying Language Modeling in Narrative Generation

- Concluding Remarks

- Further Reading and Resources

- References

Language Modeling and Generation with Deep Learning

If you’ve been following popular tech news websites in the past year, you’ve likely heard of GPT-2. This is a model created by OpenAI and is the successor to their previous model GPT. This development generated a lot of headlines since OpenAI opted for a release strategy where incrementally larger versions of the model were released over time. They claimed that the output of the full model was so good that it could be used to generate believable fake writings with ease, and thus posed a risk to public discourse. Ironically, there have since been papers published that claim such a release strategy is flawed, since these generative models are actually the best at automatically discriminating between fake and real news stories. We will discuss both of these recent developments and more in the coming sections, but first we’ll cover a quick recap of language modeling basics.

GPT-2 is an example of a language model. Language modeling is defined as the problem determining how statistically likely it is that a sequence of words exists, based on a how frequently these words appear in some set of text. In mathematical notation, this would be:

One simple way to to do this is to take a large corpus of data, and compute the likelihood of words occurring together.

A related problem is figuring out the probability of a word given a past sequence of words:

By solving this problem, it becomes possible find the next most probable word, add that to the sequence, and then predict the next most probable word of this new sequence.

By doing this repeatedly, it becomes possible to generate brand new sentences. New sentences could then be generated from these, and so on until a large body of text is created. This can useful for many important real-world applications, including:

- Creating new stories

- Quickly generating news stories

- Automating business/analytics reports

- Enabling AI to explain their behavior

GPT-2: A Dangerous AI?

As previously mentioned, there has been a lot of media hype surrounding some recent developments in the area of natural language generation. Widely dubbed “the AI that was too dangerous to release,” OpenAI’s GPT-2 model was at the center of a media firestorm that launched debates about the ethics of AI research and how to responsibly publish work in this area. The possibility for using this and other models to generate high quality fake news and other propaganda continues to be of major concern.

Fortunately, this has not yet proven to be the case, since the full model was released to the public in early November 2019 and chaos has not broken out. Nonetheless, the output and inner workings of this model are quite impressive. The primary goal of this paper was to capitalize on the idea that generalized pre-trained architectures can work well on a variety of common natural language processing tasks in a zero-shot setting. Zero-shot learning means that the model was trained without any explicit knowledge about the application domain, i.e. that there was no labeled set of training data to work with. We will now dive into the specifics of how GPT-2 and other natural language generation techniques work.

Transformer Based Architecture

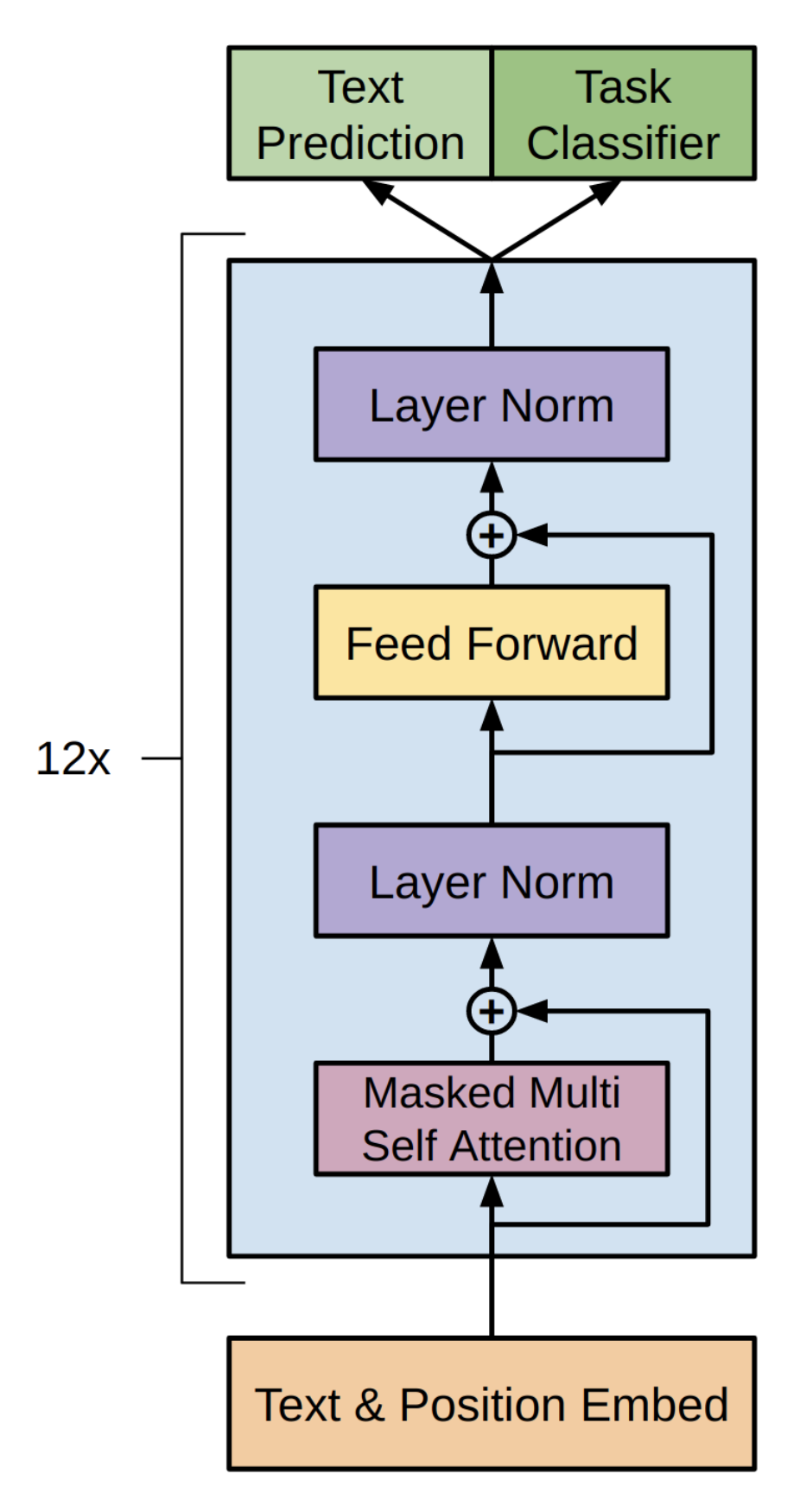

They trained a 1.5 billion parameter model, and showed that it achieved state-of-the-art results in variety of language modeling tasks. These include reading comprehension, summarization, question answering and translation. The examination of these other domains is beyond the scope of this blog, but for those that are interested, we recommend reading the original analysis provided in the paper. The architecture is mostly the same transformer model used in the original GPT-1 model (Radford et al., 2018), which in turn is very similar to the original transformer model described by this paper (Vaswani et al., 2017). A few modifications were made, including layer normalization, scaling the weights of the residual layers, and increasing the size of the vocabulary to 50,257.

The transformer architecture used in GPT-1 (Radford et al., 2018)

WebText: A New Training Dataset

In order to effectively train their model, OpenAI created a new dataset dubbed WebText. This dataset was created by scraping web pages that have been filtered or curated by humans. To this end, they gathered all documents linked to on Reddit that had at least 3 karma, i.e. had a net positive of three people that thought the document being linked to was insightful, humorous, or relevant. They ended up with 45 million links, which were then filtered to remove duplicates, remove links to Wikipedia (to avoid overlapping data with other training/test datasets), and a few other heuristics. The end results was 8 million cleaned up documents consisting of 40 GB of text. While this dataset was not released by OpenAI, the research community has worked to create a new version of it using the same methodology, and can be found here.

Try GPT-2 For Yourself

Of course, we are primarily interested in using this model for generating text. Since the language modeling task can be reformulated into a language generation task by outputtting the next token (word) with the highest probability given the previous set of tokens (words), we will now examine the output of GPT-2 in this context.

If you would like to try this generator out for yourself, there is a website that allows you to do just that: Talk to Transformer.

Given the prompt “It was the best of times”, GPT-2 gave the following output:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. A tornado swept through the small town of East San Jose and caused the death of 24 people, including a 6-year-old girl named Nipah Lane. No one knows exactly what happened on that sunny June day. The only thing everyone did know was that a little girl from Nipah Lane’s small Texas town was on life support in a hospital, that an official for the Texas State Medical Examiner’s Office was so horrified by the crime he had to cease the investigation and contact the sheriff’s office.”

This output is actually quite coherent, and because it is short enough, there is less chance of producing output where it starts to lose track of characters, their traits, and goals.

Given the prompt “Once upon a time”, GPT-2 gave the following output:

“Once upon a time there was a college student named Damon, and although he had trouble finding a job, he got this job. He had to turn in all his former self before he was given his first and only day off, but somehow Damon managed to redeem himself and get the job. But then the fear of the unknown dragged Damon into the crazed world of old monsters, hellspawn, zombies, etc. And it was then that the true nature of Damon turned to evil! Here he is trying to beat up the Zombie, and not even hesitating when he said, “and you can’t hold your breath without me.” That’s right he beats up and kills a big pile of zombies with his bare hands, then show his self in front of everyone. My favorite part of this is that he tries to make friends with a couple of the zombies, but these two are very…crazy and they don’t seem to like Kaioshin’s guts. Since you never really know what someone’s personality is like, that whole scene about them.”

The output here is of noticeably lower quality than the first passage. Due to the fact that this model uses only statistical co-occurence of words to generate the next word, there is no way for it to explicitly model the world in a logically consistent manner. Without any explicit representation of the world, it is very difficult for the model to produce results that will be consistent over increasingly long text output. With a large enough model, as is the case with GPT-2, the output “sounds” pretty good when examining localized groups of words or phrases, but it starts to go off the rails fairly quickly.

GPT-2 as a Creativity Support Tool?

Since GPT-2 generates output from a given sequence of text, incorporating it into one’s writing process would be quite straightforward, especially in the unfortunate event when writer’s block strikes. This model’s abililty to output factual output is limited, since it uses strictly statistical co-occurences when determining what words to produce next. However, for fictional or creative writing, it will always succeed in producing some path forward for your narrative. Whether this is a good path is up to the writer, and since humans are naturally good at discriminating between output they like or not, it would seem to be a natural fit.

Grover: A Fake News Generator

Grover is a new model developed by the Allen Institute for AI and the University of Washington for generating fake news stories from a prompt and some other input (Zellers et al., 2019). The output is typically convincing, and without a discerning eye, a reader that simply skims the article might be fooled into believing that the article is valid news. The authors also discuss the use of this model is detecting fake news articles, and assert that fake news generators are also the best way to automatically detect if a story is fake news.

If you would like to try generating some of your own fake news, the authors have a website where you can do just that (with some limitations due to potential for misuse in creating online propaganda).

Grover was originally developed as a way to combat the increasing prevalence of fake news by approaching this from a threat modeling perspective. In contrast to OpenAI’s approach to (at least initially) locking up the model to the public, this paper argues that the best defense against what they call neural fake news (defined as “targeted propaganda that closely mimics the style of real news”) are robust models that can generate believable fake news themselves.

Their model allows for the controllable generation of not just the news article body, but also the title, news source, publication date, and author list. Specifying the news source causes the article to have the same style of writing that is typically present at that organization. The result is fake news articles that are typically rated as more trustworthy than fake news generated by a human. They generate a news article by sampling from the probability distribution defined by:

Building and Training Grover

With the recent successes of transformer based models, the authors also use these methods for building Grover. The architecture is the same as is used for GPT-2, with a variety of model sizes that match three of the same tiers as GPT-2, including one with 1.5 billion parameters.

In order to train Grover to effectively produce fake news, they needed to create a new corpus of data that included real news articles and their associated metadata. To this end, they created the RealNews dataset. This was constructed by starting with Common Crawl data, scraping it for news articles, and then using the Newspaper Python library to extract their bodies and metadata. The body of articles used were all published between December 2016 and March 2019, with articles from April 2019 being used as the evaluation dataset. In the end, the RealNews dataset is 120 GBs of news article bodies and their associated metadata.

Generating Fake News

They evaluated their results by comparing human-written articles from reputable news sources, Grover-written articles trained with only reputable news articles, human-written propaganda, and Grover-written propaganda.

They then used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform to recruit people to evaluate the outputs based on stylistic consistency, content sensibility, and overall trustworthiness. They found that while Grover is not as good at writing propaganda as a human, it can rewrite human-written propaganda and make it seem even more trustworthy. Articles can be rewritten by taking the metadata of the human-written article, generating a new article, and then rewriting the headline. We tried generating a novel fake news article using the author’s website, and put these input parameters into Grover:

- Domain: nytimes.com

- Date: November 6, 2019

- Authors: Peter Baker

- Headline: Boris Johnson Elected President of the United States

The following fake news article was produced:

Boris Johnson Elected President of the United States

November 6, 2019 - Peter Baker

“Former London Mayor Boris Johnson has been elected president of the United States — in a swing state known for its keen interest in American political squabbles.

A Republican, Mr. Johnson defeated Democrat Lucy McBath, a gun-control advocate, in Georgia’s 6th congressional district, the Associated Press reported.

As president, he would not be part of the Federalist Society, an elite conservative group, which has embraced President Trump in the past. Mr. Johnson wrote a book with Charles Murray in 2014 calling for “intellectual ‘vigabation’ to be applied to American public affairs”; Mr. Trump dismissed it, calling Mr. Murray “a total loser.”

Mr. Johnson has also been a leading advocate for the British exit from the European Union. He was stripped of his role as foreign secretary by Prime Minister Theresa May, following the Brexit vote, following remarks he made before the vote that contrasted with that of the top London government officials. Mr. Johnson told The Guardian in 2017, “What we need to do is to make Brexit a success. In the long run we are all better off if we do this.”

Mr. Johnson also opposed the Paris climate accord.”

You can judge the output yourself, but assuming you have some knowledge about world politics, you’ll immediately know this is fake news due to the fact that Boris Johnson is British, and thus cannot be elected as president of the United States. However, the prose used here is fairly reasonable, and if you had no knowledge of this topic, you might be fooled.

Let’s try generating another article with the following parameters:

- Domain: wsj.com

- Date: August 20, 2019

- Author: John Smith

- Headline: Vaccines Cause Autism, Concludes World Health Organization

The resulting fake news article is as follows:

Vaccines Cause Autism, Concludes World Health Organization

August 20, 2019 - John Smith

NEW YORK (WKRG) -The World Health Organization (WHO) reports for the first time that vaccines caused childhood autism in a study published on Monday.

The study looked at about 650,000 children from around the world who were given vaccinations between 2000 and 2005. Vaccines were specifically offered for hepatitis A, B, diphtheria, tetanus, meningitis and pneumococcal conjugate. By 2013, 9.5 percent of the children had been diagnosed with autism, and it stayed around that level until 2009.

The WHO report, which says it is the first independent study on the connection, concludes that there is a link.

“We never made this suggestion before because we didn’t have the evidence,” Dr. Agnes Poirier, a senior author of the study, said on a conference call with reporters. “There is an overwhelming amount of evidence that says vaccines don’t cause autism. But we didn’t have the evidence. So, we decided to go back to the lab and see what we could find out.”

Poirier says the report is a “wake-up call” for the public because it officially declares a connection between vaccines and autism that some parents have feared for years. Poirier said it is hard to draw a direct connection, but the amount of vaccine-preventable diseases dropped dramatically after vaccines were introduced in the 1940s and 1950s.

Public health experts say parents need to continue to vaccinate their children. Those without insurance could also use Medicaid to pay for vaccines.

Dr. Julie Gerberding, a senior scientific adviser for Autism Speaks and former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, calls the WHO report “scientifically sound.” She hopes it will help encourage greater parental involvement in vaccines and results, especially in developing countries, where there are fewer vaccines.

“What we know from the autism literature and really from the science has been this concern has been around for 40 years,” she said. “To have this final evidence from the independent organization such as WHO would have taken considerable years to report and was very significant. Because I think it’s very important, you look at the number of children who are on their way to autism is very small and it would take many years of vaccines just to reach a majority of children.”

This article is significantly more believable and includes claims that match the headline, fake statistics to support the erroneous claim, quotes from fictional experts, and even appropriately uses acronyms. This took just a few seconds to generate, and when deployed at scale, these types of propaganda generators have to potential to overwhelm peoples’ newsfeeds. When coupled with targeted advertising, the results could be disastrous as these articles drown out the actual facts in a sea of fake news noise.

Detecting Propaganda

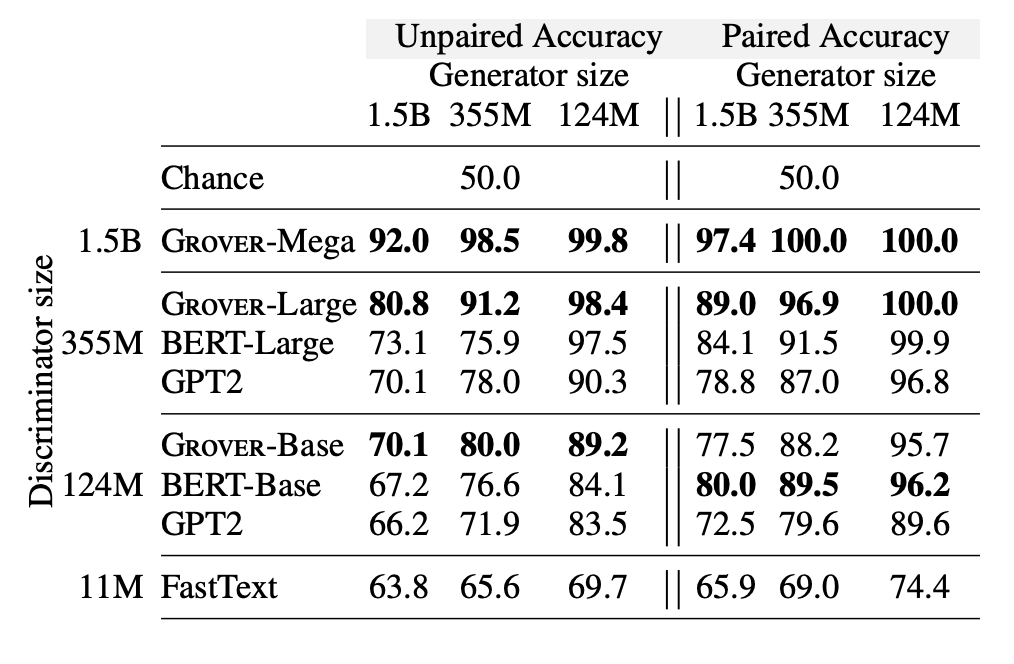

With the ability to automatically generate relatively believable propaganda articles quickly, it becomes critical that there is a way to automatically determine what is real and what is fake. To this end, the authors of this paper examined how to use Grover as a discriminator and compared its discriminative capabilities against other models including BERT (Devlin et al., 2019), GPT-2, and FastText (Joulin et al., 2017).

They use two evaluations to determine the best model for discrimination. The first is the unpaired setting, in which the discriminator is given a single news article at a time, and must determine if it was written by a human or a machine. The second is the paired setting, in which the discriminator is given two news articles with the same metadata, one of which is written by a human and one which was written by a machine. The model must then determine which one has a higher probability of being written by a machine. The results were as follows:

Figure from (Zellers et al., 2019)

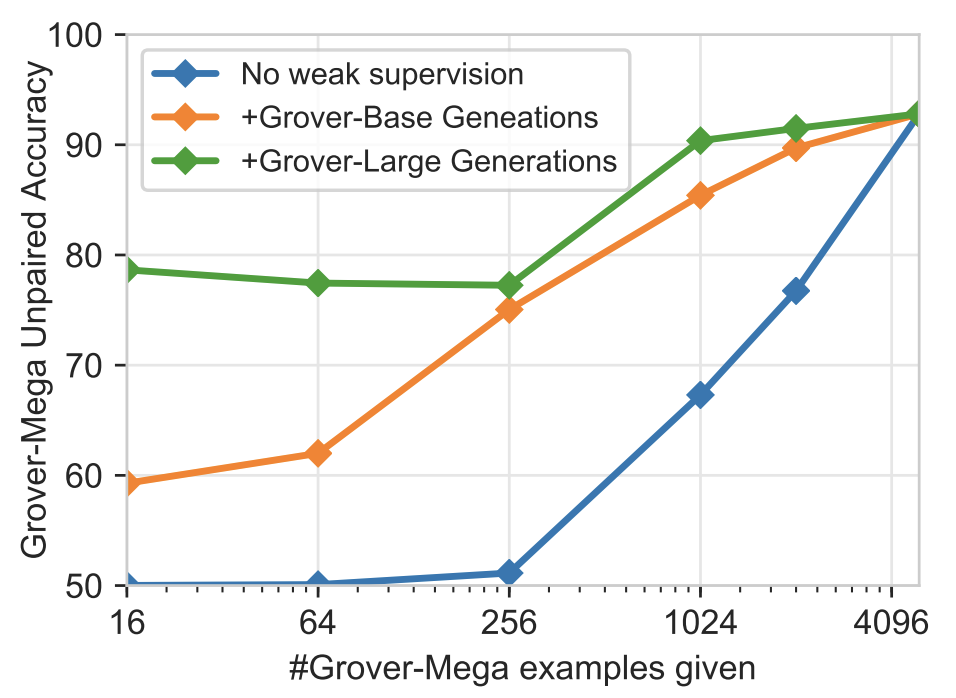

Interestingly, Grover does the best at determining whether its own generations are written by a machine or not, despite being unidirectional (i.e. it only looks at previous words in a sequence when predicting, rather than looking at previous and successive words, as with BERT). Perhaps more intuitively, they found that as more examples from the adversary generator are provided to the discriminator, the better Grover does at determining whether it is fake news or not, as shown in the following diagram:

Figure from (Zellers et al., 2019)

The Future of Fake News

As these language generators become increasingly powerful and more convincing, it seems inevitable that malicious actors will utilize these to rapidly spread misinformation across the globe. The authors argue, and provide evidence, that the best defense against neural fake news is a model that can generate this type of fake news. Consequently, they have released the 1.5 billion parameters version of the model to the public.

However, even if we have the tools to debunk these stories as fake news automatically, the odds of social media platforms actually deploying these tools is depressingly low, as platforms like Facebook, Google, and YouTube have argued that it is not their job as a platform to filter their users’ speech. As these neural fake news generators become more robust and widely available, anybody with a malicious (or simply ignorant) agenda will be able to generate a flood of misinformation. It would seem then that the only way to actually combat the misuse of these tools is with not only responsible research, but through systemic changes to the media platforms, either through internal change or governmental regulation.

Evaluating Language Models

In order to gauge progress in a research area, it is important that there are rigorous evaluation methods that allow for results to be directly compared to each other. In this section, we will cover a few such methods for evaluating language models.

Perplexity

One way to determine how well a language model works is with perplexity. Perplexity is the inverse probability of the test set, normalized by the number of words (Brown, et al. 1992). In essence, minimizing perplexity is the same thing as maximizing the probability. In this way, a low perplexity score indicates that the sequence of words being examined is probable based on the current language model from which probabilities are being drawn.

Does Perplexity Work Well?

Perplexity can be good for automatically measuring plausibility of the prose (i.e. whether it likely that certain words follow each other), but it is not always useful for applications like narrative generation. This is because readers typically want to see a certain level of familiarity mixed with some novelty and surprise. Perplexity assigns higher scores to outputs that are more predictable. As a result, this might decent measure when determining if a sequence of words is grammatically correct or “sounds” good, but not if we use it to evaluate the events in a story where it is desirable to have unexpected events happen.

BLEU Score

The Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) score (Papineni, et al. 2002) was originally designed as a means of evaluating machine translation systems by determining how well two sentences in different languages matched by using an n-gram comparison between the two. However, this metric can be adapted for use in evaluating generated language. Rather than evaluating two sentences across languages, a machine generated sentence is evaluated based on its similarity to the ground truth reference sentence written by a human. In this way, a higher BLEU score indicates that the machine generated sentence is more likely to have the same features as a sentence produced by a human.

Human Evaluation

Automated metrics are a nice initial means for testing a model, but seeing as humans are already (ideally) masters of language, the ultimate test is putting it in front of people and letting them evaluate it. These types of evaluations are typically done less frequently due to the associated monetary costs, but they are critical for determining the believability and quality of the generated language.

Applying Language Modeling in Narrative Generation

Narrative generation has a long, and storied past that spans multiples eras of artificial intelligence research, and the research in this area often goes hand-in-hand with language generation. Effective natural language generation has many of the same requirements in that the output is plausible and has coherence among the many entities and events involved in the text. In this section, we will examine some recent major work in this area.

Planning Based Generation

Prior to much of the current deep learning and statistical models used today, there were significant efforts dedicated to symbolic artificial intelligence that focused on using searching and planning algorithms to produce natural language stories. Work in this area dates back to the 1970s, with Tale-Spin, a system from the Yale AI Group that simulated an artificial world and the agents within in order to create a plausible story (Meehan, 1977). For those looking for an in-depth survey of this area of research, we recommend this survey (Young et al., 2013).

In this area of research, it is common to start by building a domain model. This is a description of a fictional world that defines the entities that exist within it, the actions they can take to alter the state of the world, the objects in the world, and the places they exist. From these domain models, traditional planning algorithms (Riedl and Young, 2010) or case-based reasoning (Gervas et al., 2004) can be used to generate new stories. Planning techniques will find a path through the space of possible worlds, keep track of the entities, their actions, and the state of the world. In this way, a logical series of events can be generated that form a coherent narrative. Case-based reasoning techniques will use examples of past stories (or cases) and adapt them to fit the narrative at hand.

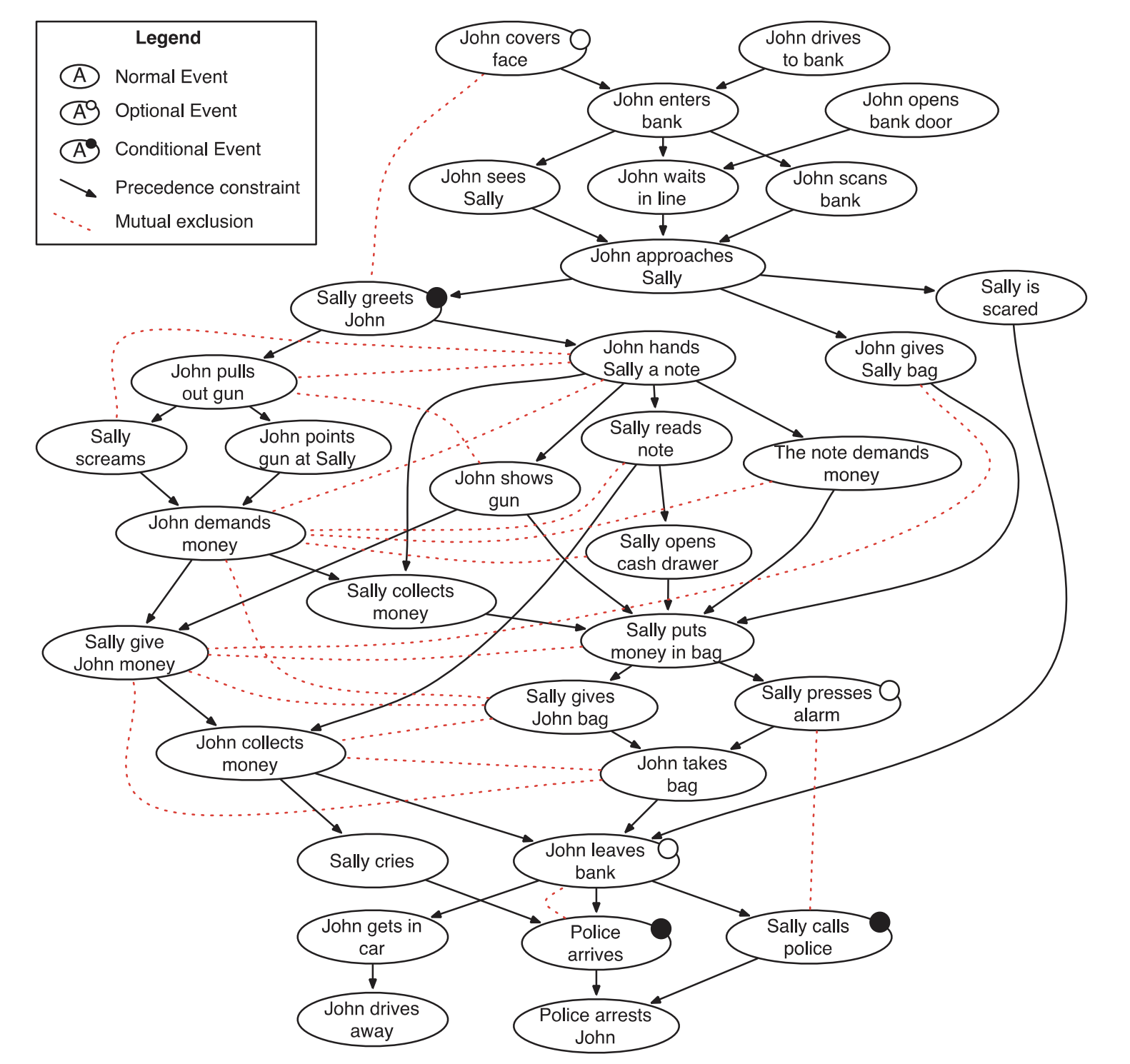

A major limitation of planning-based approaches is that they require significant amounts of human-authored knowledge about a variety of situations in order to effective. Thus, while they can produce effective and interesting narratives, they have difficulties scaling up and are often limited in scope to specific scenarios. In an attempt to overcome this issue, one recent work (Li et al., 2013) presents a method for automatically building a domain model. Rather than engineering it by hand themselves, the authors sought to use crowdsourcing to build up a corpus of narratives for a domain, automatically generate a domain model, then sample from this space of stories based on the possibilities allowed by the model. They use a plot graph representation that provides a model of logical flows of events and their precursor events that must occur before a given event. With these graphs in place, traversal can be done to produce a logically coherent sequence of events / narrative. The resulting plot graph for a bank robbery domain would look as follows:

Figure from (Li et al., 2013)

Interactive Narratives

In addition to static narrative generation, there has been much work on creating narratives that allow for a person to interact with them and change the course of the story through their actions. This paradigm occurs most frequently in video games, but there are other instances including choose-your-own-adventure books, table-top role-playing games (like Dungeons and Dragons), and interactive movies (such as Netflix’s Black Mirror: Bandersnatch). Interactive narrative generation differs from static narrative production in that the storylines must be highly modular in order for reasonable plot lines to develop naturally according to the human user’s actions.

To this end, interactive narratives typically employ a Drama Manager (Guzdial et al., 2015), which is a central agent that manages the story and directs the plot and agent actions in order to maximize a set of author provided heuristics and improve the user’s experience. The techniques employed by the Drama Manager can be highly variable, depending on the goals of the interactive simulation, and many different approaches to producing interactive narratives have been proposed. For an overview of the major challenges and proposed solutions in interactive narrative generation, we recommend this survey paper (Riedl and Bulitko, 2013), or this chapter from the Handbook of Digital Games and Interactive Technologies (Cavazza and Young, 2017).

This problem has typically been approached from a planning perspective, with extensive and intricate planning systems developed to produce satisfying interactive narratives. The approaches utilized follow the ones mentioned in the previous section on planning based generation. However, there are other approaches that have been explored due to the shortcomings conventional planning algorithms. (Porteus et al., 2010) developed a constraint-based system that applies state trajectory constraints to each state in the world. They effectively decompose the narrative generation problem into a set of sub-problems, each of which can be solved by ensuring that a set of constraints are satisfied for that smaller problem. The sequence of narrative events for each of these subproblems can be composed into a larger single narrative. Then, if certain world constraints are modified by user interaction, subproblems can be resolved quickly and individually.

Others have looked to deep learning for developing approaches to generating interactive narratives. In one paper (Wang et al., 2017), the authors train a deep Q-network (Mnih et al., 2015) in order to create a set of narrative events that are tailored to the player based on the actions they are taking in the simulation. In another paper (Wang et al., 2018), the authors create simulated humans with deep recurrent highway networks (Zilly et al., 2017) in order to explore the spaces of possible narratives that would typically be encountered by a person. In this way, the human user’s behavior can be better predicted and accounted for when determining what path the narrative should follow moving forward.

Neural Network Based Generation

The methods discussed in the previous section for producing interactive narratives were not focused on generating natural language text output, but rather ensuring that a sequence of events are generated in accordance to a user’s input. In this section, we will return to techniques for producing textual narratives by using language models and neural networks.

As previously discussed, language models such as GPT-2 and sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) (Sutskever et al., 2014) architectures have recently been used for generating text output, but their use in creating coherent narratives has been limited. While traditional planning algorithms have difficulty with generating language that reads nicely, they excel at producing narrative structures with high logical coherence. The reverse is true for these deep learning language models. There is much recent work to rectify this issue by breaking up the natural language generation process into two parts. The first part creates some set of events or representation of the narrative structure, which can be thought of as a sort of planning phase. The second part then translates this into natural language text and a final narrative.

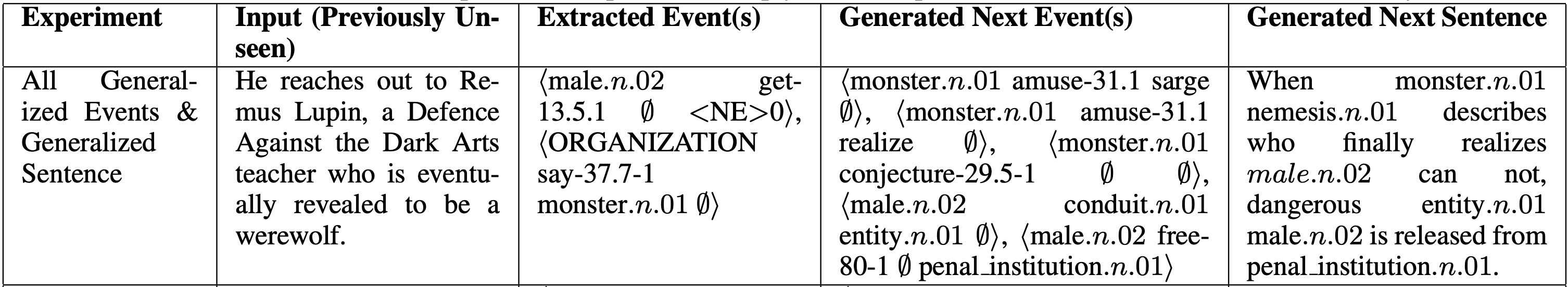

One paper (Martin et al., 2018) uses seq2seq models for open story generation, which is defined as the “problem of automatically generating a story about any domain without a priori manual knowledge engineering.” They use this two-phase approach in which they first generate events and then produce sentences based on these events. The first phase utilizes a seq2seq model to generate events. The event representation used in this work is a 5-tuple, consisting of the subject of the verb, the verb, the object of the verb, a wildcard modifier, and a genre cluster number. The set of events with which to train the model were extracted from a corpus of movie plot summaries from Wikipedia (Bamman et al., 2014).

For the second phase, they create the event2sentence network, another seq2seq network that was trained on a corpus of stories and the events contained within. This network learns to translate these 5-tuple event representations into natural language sentences.

They also experimented with using events containing more general terms for the entities involved by using WordNet (Miller, 1995). WordNet provides a way to find more general terms for a given word. For example, if the word is “hello,” then WordNet representation for it would be hello.n.01, and a more general/abstract term would be greeting.n.01.

In order to evaluate their output, they use perplexity to determine how well this method generates coherent event sequences and natural language text. However, it seems that perplexity would be a poor metric in narrative generation since it measures the predictability of a sequence, with more predictable sequences being rated as better. Using this metric seems counterintuitive since people typically want some element of surprise in their stories. In addition to this metric, they use the BLEU score for evaluating both of the networks. The authors note that the BLEU score make little sense for evaluating the event2event network, and is better suited for evaluating the event2sentence network since this can be viewed as a translation task.

An example of this paper’s output is shown below:

Figure of the results from (Martin et al., 2018)

Using a similar two-phase approach, (Xu et al., 2018) proposes a method for generating a narrative story based on a short description of a scene or event. They use a reinforcement learning method to generate the skeleton (a set of the most critical phrases/words), and then expand the skeleton into fluent sentences. The reinforcement learning process rewards good skeletons in which all key information is contained, while other information is ignored. Bad skeletons, which contain too much detailed information or lack key information, are punished. They uses human evaluation in addition to the BLEU score, and found that their model produced higher (i.e. better) BLEU scores than previously proposed models.

Some examples of their output is as follows:

Input 1: The park was filled with beauty.

Output 1: The trees were very sparse. There were also some flowers.

Input 2: The bride was driving to the wedding.

Ouput 2: The groom and groomsmen watched the bride. They kissed and shared their pictures.

Another paper, this time from Facebook AI Research (Fan et al., 2018), proposes what they call hierarchical neural story generation, where first a prompt (i.e. a sentence) is generated, and then a seq2seq model is conditioned on this prompt to generate the rest of the story. They introduce a gated self-attention mechanism that allows for the neural network to be conditioned on previous outputs at different time-scales. The model they use to generate the story is a convolutional seq2seq model, where the decoder is supplemented with this self-attention mechanism to allow the model to attend to any previously seen word it generated. In this way, they are able to capture some long-range coherency within the model itself.

They created a new training corpus by scraping Reddit’s /r/WritingPrompts forum where users write short stories based on a short description. They gathered three years worth of prompts and cleaned them for use. The end results are quite good, as shown in the following example taken from their paper:

Prompt: Aliens start abducting humans

“It has been two weeks, and the last of my kind has gone. It is only a matter of time until there will be nothing left. I’m not sure what the hell is going on… I can’t think. I can hear a distant scream. I think of a strange, alien sound. I try to speak, but am interrupted by something, something that feels like a drum, I ca not tell. I mean I’m just a little bit older than an average human. But I can, and I can feel the vibrations . I hear the sound of a ship approaching. The ground quakes at the force of the impact, and a loud explosion shatters the silence.”

Similar to Fan et al’s work, another paper (Yao et al., 2019) proposes a hierarchical generation framework that combines plot planning with text generation to create a story based on a given title. They introduce two methods for planning out the plot: dynamic schema, which alternates between producing a plan for the story and generating the text in the story, and static schema, which does all of the plot planning prior to generating any of the final story text.

The static schema method uses two seq2seq models: one for generating the plot and one for generating the text. The dynamic scheme method uses the method from one of their previous papers (Yao et al., 2017), which used a seq2seq model augmented with bidirectional gated recurrent units. Additionally, they trained their model on the ROCStories corpus (Mostafazadeh et al., 2016), which contains 98,161 short, commonsense stories. These stories consist of five sentences that contain causal and temporal relationships in everyday situations.

Additionally, they use both objective and subjective metrics to evaluate their output. A novel objective evaluation metric is introduced that quantifies the diversity of language within and between stories that are generated, where lower scores are better. The subjective analysis tasked Amazon Mechanical Turkers to choose between the output of a baseline model and their new model based on the story fidelity, coherence, interestingness, and overall user preference. They find that the static schema method produces results that are superior to not only prior work, but also their dynamic schema method.

An example of their output is as follows:

Title: The Virus

Dynamic Schema

Storyline: computer → use → anywhere → house → found

Story: I was working on my computer today. I was trying to use the computer. I couldn’t find it anywhere. I looked all over the house for it. Finally, i found it.

Static Schema

Storyline: work → fix → called → found → day

Story: I had a virus on my computer. I tried to fix it but it wouldn’t work. I called the repair company. They came and found the virus. The next day, my computer was fixed.

The Future of Narrative Generation

The current state of research in this area seems to be focusing on utilizing multiple stages in the language generation process. This would mirror how most humans tend to write narratives: first with a planning phase (how in-depth this process is depends on the writer and their goals), and then turning this plan into a body of text that achieves their narrative goals. Producing a coherent narrative is just one piece of the puzzle though. In order for a story to have real impact on the reader, it needs to be able to elicit certain emotions in the audience, as well as hold their attention with compelling prose. To this end, it also seems prudent to incorporate research ideas from affective computing and sentiment analysis in the generation or planning process. For now it seems likely that the focus will remain on producing coherent narratives, as this is still a major unsolved challenge despite the progress we have examined in this post.

Concluding Remarks

This area of research remains highly relevant and the ultimate goal of creating high quality natural language text still seems a ways off. Creating such a system would be a major step towards to producing artificial general intelligence since language is most often the medium through which humans reason about the world, and the production of narratives can involve simulating agent behavior in complex environments. The creation of such a language system would have no doubt have massive implications for society at large, both positive and negative, particularly with regards to producing endless amounts of entertainment or propaganda.

Further Reading and Resources

References

- Bamman, David, Brendan O’Connor, and Noah A. Smith. “Learning latent personas of film characters.” Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). 2013.

- Brown, Peter F., et al. “An estimate of an upper bound for the entropy of English.” Computational Linguistics 18.1 (1992): 31-40.

- Cavazza, Marc, and R. Michael Young. “Introduction to interactive storytelling.” Handbook of Digital Games and Entertainment Technologies (2017): 377-392.

- Devlin, Jacob, et al. “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding.” Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). 2019.

- Fan, Angela, Mike Lewis, and Yann Dauphin. “Hierarchical neural story generation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.04833 (2018).

- Gatt, Albert, and Emiel Krahmer. “Survey of the state of the art in natural language generation: Core tasks, applications and evaluation.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 61 (2018): 65-170.

- Gervás, Pablo, et al. “Story plot generation based on CBR.” International Conference on Innovative Techniques and Applications of Artificial Intelligence. Springer, London, 2004.

- Guzdial, Matthew, et al. “Crowdsourcing Open Interactive Narrative.” FDG. 2015.

- Joulin, Armand, Edouard Grave, and Piotr Bojanowski Tomas Mikolov. “Bag of Tricks for Efficient Text Classification.” EACL 2017 (2017): 427.

- Li, Boyang, et al. “Story generation with crowdsourced plot graphs.” Twenty-Seventh AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2013.

- Martin, Lara J., et al. “Event representations for automated story generation with deep neural nets.” Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2018.

- Miller, George A. “WordNet: a lexical database for English.” Communications of the ACM 38.11 (1995): 39-41.

- Meehan, James R. “TALE-SPIN, An Interactive Program that Writes Stories.” IJCAI. Vol. 77. 1977.

- Mnih, Volodymyr, et al. “Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning.” Nature 518.7540 (2015): 529.

- Mostafazadeh, Nasrin, et al. “A Corpus and Cloze Evaluation for Deeper Understanding of Commonsense Stories.” Proceedings of NAACL-HLT. 2016.

- Papineni, Kishore, et al. “BLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation.” Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting on association for computational linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2002.

- Porteous, Julie, Marc Cavazza, and Fred Charles. “Applying planning to interactive storytelling: Narrative control using state constraints.” ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 1.2 (2010): 10.

- Radford, Alec, et al. “Improving language understanding by generative pre-training.” URL https://s3-us-west-2. amazonaws. com/openai-assets/researchcovers/languageunsupervised/language understanding paper. pdf (2018).

- Radford, Alec, et al. “Language models are unsupervised multitask learners.” OpenAI Blog 1.8 (2019).

- Riedl, Mark Owen, and Vadim Bulitko. “Interactive narrative: An intelligent systems approach.” Ai Magazine 34.1 (2013): 67-67.

- Riedl, Mark O., and Robert Michael Young. “Narrative planning: Balancing plot and character.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 39 (2010): 217-268.

- Sutskever, I., O. Vinyals, and Q. V. Le. “Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks.” Advances in NIPS (2014).

- Vaswani, Ashish, et al. “Attention is all you need.” Advances in neural information processing systems. 2017.

- Wang, Pengcheng, et al. “Interactive Narrative Personalization with Deep Reinforcement Learning.” IJCAI. 2017.

- Wang, Pengcheng, et al. “High-Fidelity Simulated Players for Interactive Narrative Planning.” IJCAI. 2018.

- Xu, Jingjing, et al. “A skeleton-based model for promoting coherence among sentences in narrative story generation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.06945 (2018).

- Yao, Lili, et al. “Towards implicit content-introducing for generative short-text conversation systems.” Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 2017.

- Yao, Lili, et al. “Plan-and-write: Towards better automatic storytelling.” Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 33. 2019.

- Young, R. Michael, et al. “Plans and planning in narrative generation: a review of plan-based approaches to the generation of story, discourse and interactivity in narratives.” Sprache und Datenverarbeitung, Special Issue on Formal and Computational Models of Narrative 37.1-2 (2013): 41-64.

- Zellers, Rowan, et al. “Defending Against Neural Fake News.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.12616 (2019).

- Zilly, Julian Georg, et al. “Recurrent highway networks.” Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning-Volume 70. JMLR. org, 2017.