A Short Summary of Automatic Summarization

Image courtesy of medium.com

In the past decade, neural networks have spearheaded a renewed interest in AI due to their ability to perform quite well in tasks that involve a lot of implicit knowledge such as computer vision and NLP. Within NLP (specifically generation and understanding), automatic summarization is one of the areas where a lot of advances have been made. The purpose of this post is to provide a brief introduction (one might say, a brief summary) to the field of automatic text summarization. Given that the field has a quite extensive history, we will be focusing mostly on deep learning methods.

Table of Contents

What is Summarization

Automatic summarization is one of the most important tasks that has been explored in the fields of NLU/NLG, with interest in it for almost 20 years (Hahn and Mani 2000). The general definition of it is largely agreed upon: summarization involves transforming some text into a more condensed version of the original one while remaining faithful to the original text. For instance, we can remove sentences, rephrase sentences, or merge sentences (Jing 2002).

There are multiple paradigms in which summarization occurs, such as:

- Sentence-to-sentence: We have one sentence and we try to find a summarization of it; often this involves rephrasing the sentence in a shorter manner.

- Paragraph-to-paragraph: We have a paragraph and try to “write” a shorter paragraph. This can involve either identifying the most important sentences of the paragraph, or rewriting a smaller paragraph.

- Multiple documents: This might be the paradigm with largest scope since it involves taking multple documents (often with similar or repeated ideas/facts) and having a more succint summarization.

Extractive Summarization

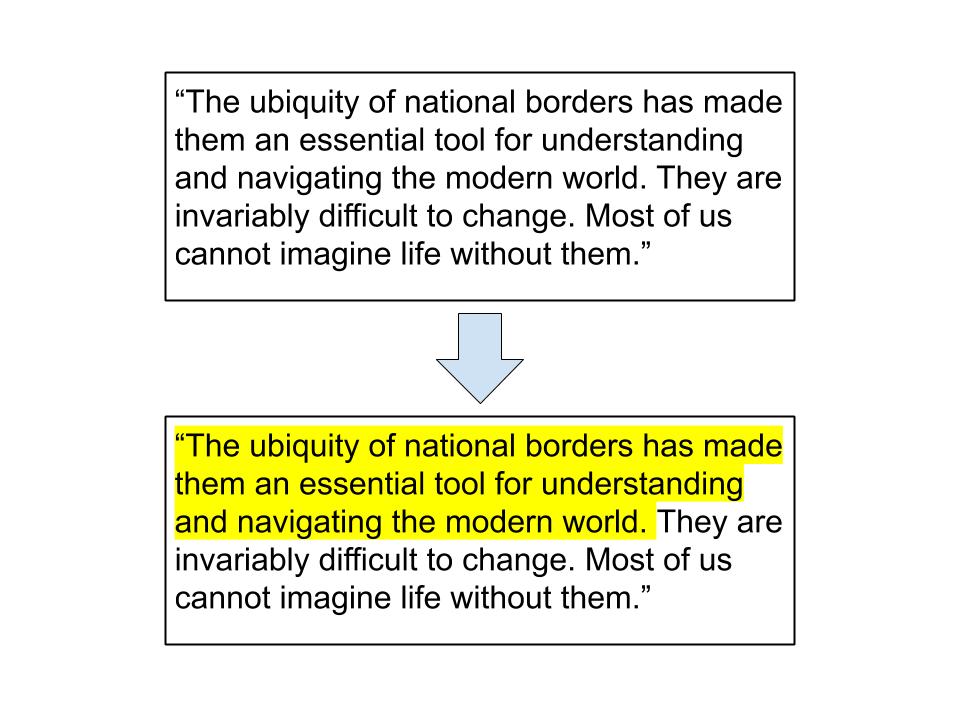

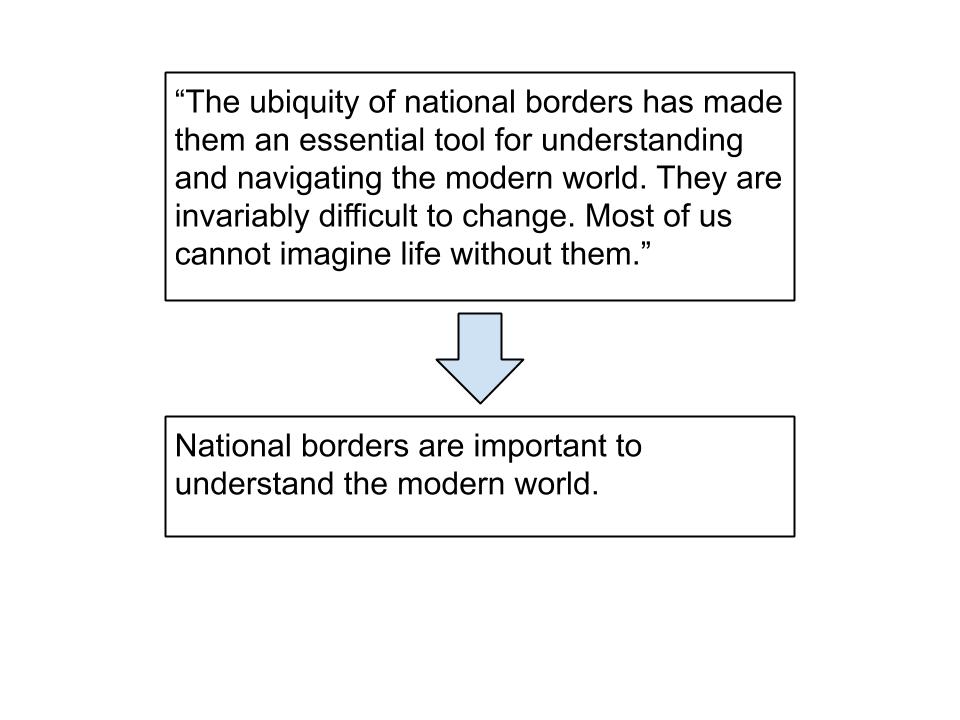

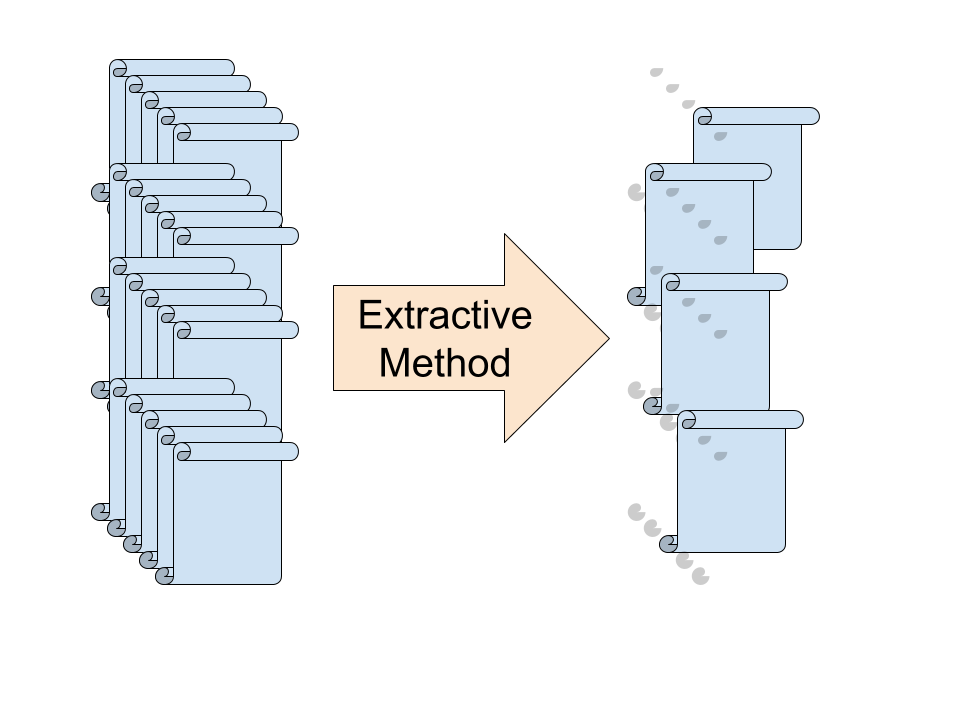

There are two main approaches that exist to summarization: extractive and abstractive. Extractive summarization involves selecting the most important parts of the source text. We can think of it as having a machine read a textbook and highlight the most important passages of the book. This approach to automatic summarization is how the problem has been approached historically (Udo and Mani 2000).

Example of extractive summarization, source text from https://thecorrespondent.com/147/borders-dont-just-keep-people-out-they-define-their-worth/19260022320-1d1d8615

Abstractive Summarization

Abstractive summarization is a setup that is less restrictive than extractive, since you are no longer limited to just using sentences in the source text. If extractive is like using a highlighter on some text, abstractive involves reading the text and taking some notes about the text.

Example of abstractive summarization

In some instances, allowing the model to have more control over its generated text gives it more powerful tools; for instance, it can shorten or combine sentences and it could even rephrase sentences in a clearer way. However, this freedom often makes the problem harder since it involves having to generate new sentences, adding in a more complex generative component to this problem.

Evaluation

Datasets

In the field of automatic summarization, some of the most commonly used data sets are the following:

- Document Understanding Conferences (DUC): These conferences ran from 2001-2007 and had datasets for each of those years, with the most common ones being for 2002 and 2004. Each set of documents contains the documents themselves along with summaries for each. Though the datasets are often not large enough to be used for training, they are used primarily for testing the performance of systems. The link for the datasets is here

- CNN/DailyMail (Hermann et al. 2015): The dataset is a collection of scraped news stories from CNN and the Daily Mail. Details of the dataset are in the original paper and in this Github repo.

- English Gigaword (Graff et al. 2003): This is one of the largest news documents dataset, with over 1 million documents. Often, the annotated version (Napoles, Gormley, and Van Durme 2012) is used since it includes additional data such as tokenized sentences and name-entity recognition.

- Scraped datasets: A lot of times, datasets are created by the authors of the methods by scraping the web for their desired datasets. This often leads researchers to have datasets that have readily available summaries, such as news sources or encyclopedia-style web pages. For instance, (Liu et al. 2018) utilized Wikipedia articles as a dataset for summarization, with the article references and the web searches as the input text, and the first Wikipedia article as the target summary.

A note on datasets

An important issue that has been noted by researchers (Kryściński et al. 2019) is that the relience on news articles for summarization stems from the following:

- These have examples of “good” summaries, namely the titles

- There are multiple sames of the same news story, allowing for more training data

- News articles have a structured setup (i.e. the important information precedes the least important one)

Though this might allow the model to more easily learn news summarization, not all text that we want to summarize has said structure. Keeping this caveat in mind is necessary when using these methods since the models might not be able to properly generalize to other text sources.

Metrics

Generative machine learning has a problem that discriminative machine learning has managed to solve more successfully: useful metrics for evaluation. For instance, if we say that a model has 95% accuracy when classifying an image as a dog or not a dog, it is clear to us what that means and if the model is good or not.

Generation, however, presents a much more difficult task since we need to figure out a way of identifying if a generated data point is “good”. Furthermore, the fact that there exist multiple “good” samples makes it a lot more difficult. Going back to the dog example, either it is a dog or not, and one answer is correct. However, if we were trying to generate a model that can create dogs, this becomes more difficult since there are multiple “correct” dogs.

Automatic text summarization suffers from this problem as well. Not only are there multiple correct summaries, but we also have to ensure that the metrics we choose highlight what we think is “good” of a good summary.

Perplexity

Though not frequently used, perplexity (Brown et al. 1992) is still used to evaluate some automatic summaries. Perplexity aims to measure how likely a sentence is, with a higher perplexity indicating that the sentence is less likely. This measure is mostly used for abstractive summarization since it also involves having to create new sentences.

ROGUE(s)

One of the most widely used metrics is the Recall-Oriented Understudy for gisting Evaluation, commonly known as ROGUE (Lin 2004); this metric was elaborated especifically for evaluating summaries. In reality, ROGUE various different sub-metrics that are used, with the original paper introducing four of these: ROUGE-N, ROUGE-L, ROUGE-W, and ROUGE-S. Additionally, a lot of these can be oriented towards recall, precision, or f-score. The specifics of these are quite different, but they all operate under the same basic logic: we compare a proposed summary sentence with a reference summary and calculate how “good” the proposed summary is based on some similarity metric with the reference one. Another similarity between these metrics is that a higher ROGUE score indicates a “better” summary.

Note that in addition to the original ROGUE metrics, there has been a lot of subsequent work focusing on having additional ROGUE metrics (ShafieiBavani, 2018).

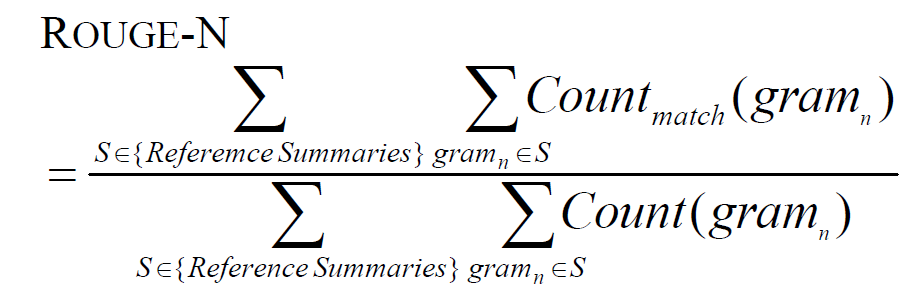

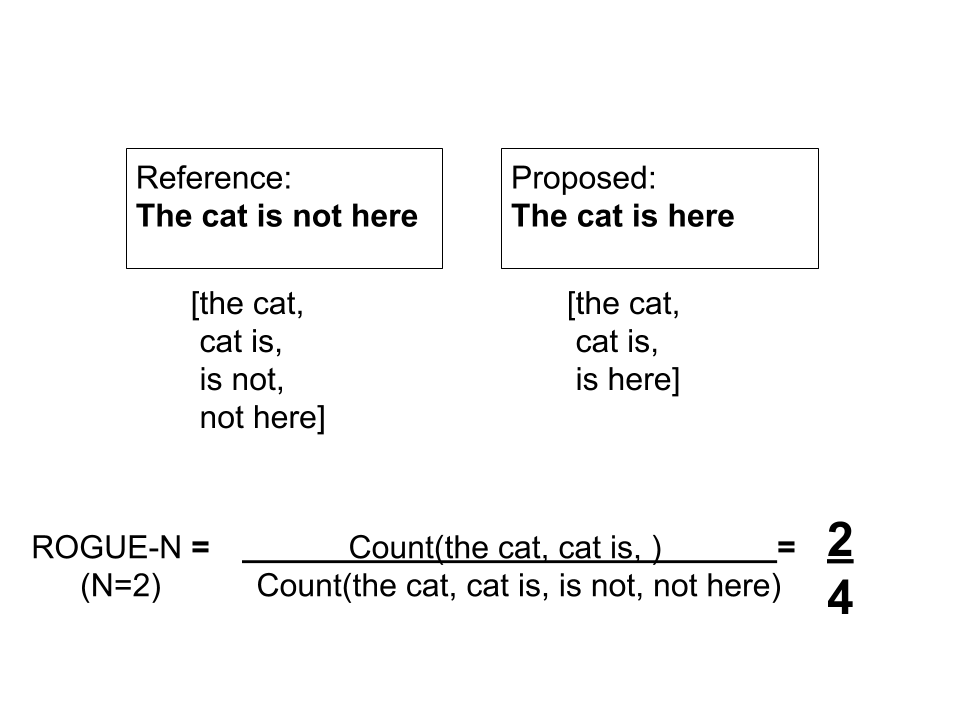

ROGUE-N

ROGUE-N is based on the notion of recall, meaning that it measures how well the proposed summary can recall the appropriate elements of the reference summary. It obtains the n-grams of both summaries and obtains the ratio of the n-grams in common and the n-grams in the reference summary.

ROGUE-N also allows for multiple reference summaries by obtaining the n-grams between the proposed the summary and each of the reference summaries. The equation is as follows

Rogue-N equation, from (Lin 2004) paper

where Reference Summaries are the summaries we know are correct, Countmatch(gramn) are the number of matching n-grams that occur in both the reference and the proposed summary, and Count(gramn) are the number of n-grams in the reference summaries.

Rogue-N example, where N=2

ROGUE-L, ROGUE-W, and ROGUE-S

The other three ROGUE metrics measure different aspects of similarity, since ROGUE-N only focuses on recall and on number of common matches. Furthermore, these three ROGUE scores can be recall, precision, or f-score oriented.

- ROGUE-L looks at the longest common subsequence of words between the two summaries

- ROGUE-W focuses on the weighted longest common subsequence, where we give higher weight to continuous subsequences rather than subsequences with a lot of discontinuities.

- ROGUE-S is similar to ROGUE-N, but rather than looking at N-grams, it focuses on skip-grams.

Fact-Based Metrics

Recall that in our definition of summaries, we said that summarization involves “transforming some text into a more condensed version of the original one while remaining faithful to the original text”. While it is easy to see how to create a condensed text (e.g. remove unnecessary words from the text), remaining “faithful” to the original text can be quite hard. ROGUE aims to stay faithful to the text by ensuring that similar words are used. Yet, we often want summaries that use simpler synonyms rather than permeating the generated document with the original’s superfluous and indecepherable lexicon. To that end, fact-based metrics of success have been proposed and used by researchers who want to ensure that the summary does not make any inaccurate statements or it omits any important information.

The hardest part of evaluating factual accuracy is that we would need to have an automatic way of comparing factual accuracy between two texts. The simplest way of checking for factual correctness is by manually having humans look at the facts from the original sentence and seeing if the summary reflects the same (Cao et al. 2018). Though effective, this method seems to be hard to scale up.

Recently, there has been some work in trying to automate this process. One of the more recent works has trained a model to be able to extract facts from text (Goodrich et al. 2019). By taking this approach, they are able to extract facts from the original and the summary text, and compare these two with simple precision and recall metrics. The repo for the model and the data should be available in the future here.

Methods

For each of the main approaches within extractive and abstractive summarization, we will be focusing on explaining and understanding one model that employs said methods. Though this limits the scope of the survey, we believe that these examples highlight the main features of the approaches and that understanding these examples leads to an easier understanding of similar work.

Background on Methods

The main deep learning techniques that are used in summarization techniques stem mostly from the techniques used in NLP tasks. Among these, the most commonly used are:

- RNN’s, different types of recurrent cells (e.g. GRU’s and LSTM’s), and bidirectional variants of these

- Attention mechanisms, often mixed with RNN’s

- Transformers

- Word embeddings to obtain features from text input

- CNN’s in order to have some context about each word

- Greedy and beam search in order to generate sequences of words (for more on beam search, watch this video by Andrew Ng)

Extractive Methods

Extractive summarization has had a long history of being developed, with a lot techniques outside the field of deep learning (Allahyari, et al. 2017). Within deep learning, the problem of extractive summarization is often viewed as either a supervised learning approach in which we try to classify if a sentence should be in the summary, and a reinforcement learning one where we have an agent decide if a sentence should be selected.

Classifier/Selector Approach

There have been multiple attempts at using classifying/selecting procedures to decide if a sentence should be selected or not (Nallapati, Zhou, and Ma 2016) to create summaries. One of the most involved examples is (Yin and Pei 2015), where they aim to optimize sentence selection based on informativeness and redundancy.

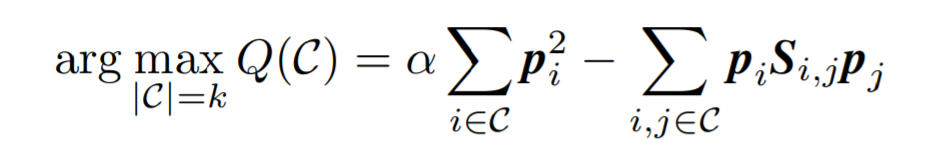

The authors of the paper develop a selection algorithm that is proven to be near-optimal in maximizing sentence prestige while ensuring that redundancy is kept low. A prestige vector is calculated for each sentences by using the PageRank algorithm (more information on it here) on a similarity matrix; the similarity matrix is also used to ensure that redundancy between sentences is low. In more mathematical terms, they aim to maximize

Objective function of selecting algorithm

where C is a collection of k sentences (i.e. our candidate sentences), $\alpha$ is a hyperparameter that increases the importance of sentence prestige as $\alpha$ increases, pi is the prestige vector of sentencei, and Si,j is the similarity between sentences i and j. The first term of the function refers to the prestige of adding that sentence, and the second term refers to the redundancy in adding that sentence when taking into account the sentences that have already been selected.

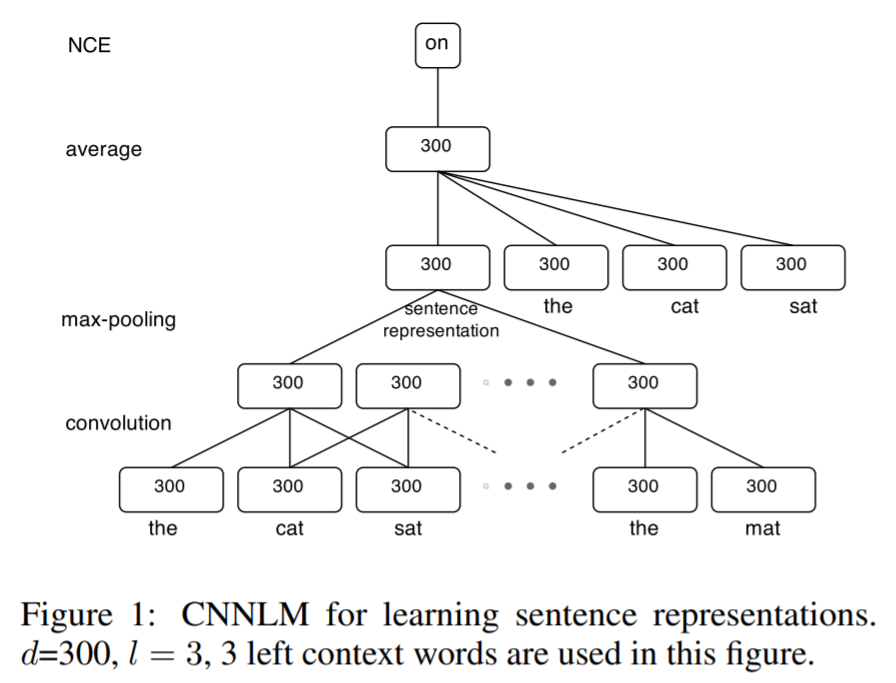

To calculate the similarity matrix, they use feature vectors obtained via a CNN network that does language modeling on a sentence to predict the next word. Then, by using the intermediate sentence representations of this task, they derive similarity measures between sentences.

CNN for Language Modelling

The dataset that they use for training the CNN is the English Gigawords dataset along with some additional DUC data, and they run experiments on DUC-2002 and DUC-2004. They go on to show that their ROGUE-N (N=1, N=2) and ROGUE-SU4 scores are higher than other baselines.

Though this paper’s approach is quite interesting, having to construct a matrix that is NxN, where N is the number of sentences, might not be scalable when having to deal with multiple documents. Furthermore, the extractive nature of it might interrupt the narrative flow or the meanings between the sentences. Finally, though the unsupervised approach helps translate this model more easily to new domains, not having a “reference summary” during training might cause the model to not really “know” what a good summary looks like.

Reinforcement Learning

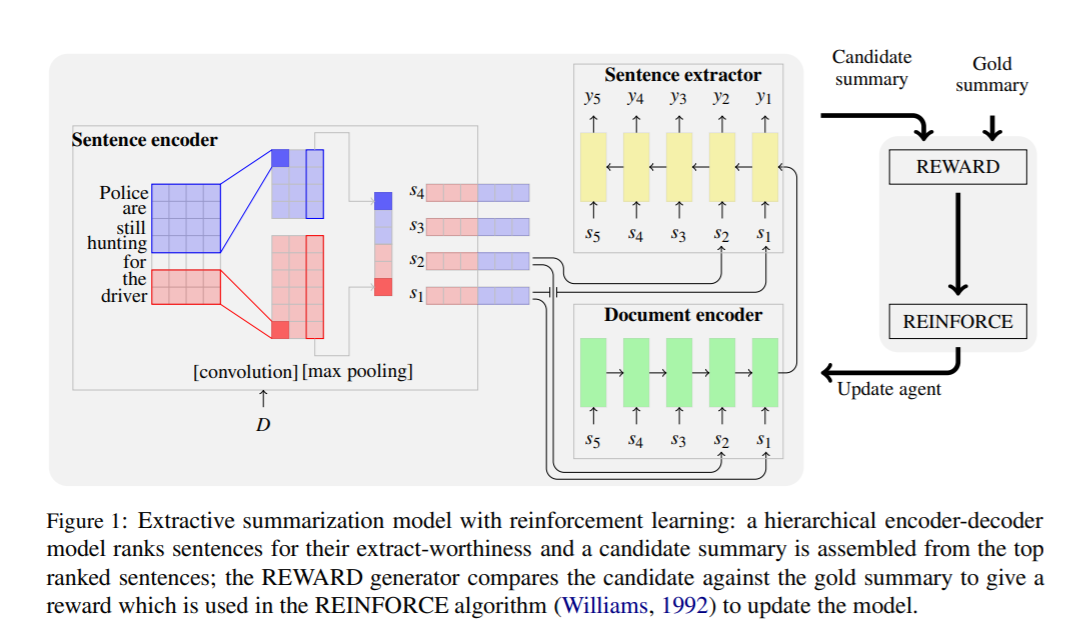

Another approach that has been taken to optimize the selection of sentences is to use a reinforcement learning set up (Narayan, Cohen, and Lapata 2018) (repo here). In this work, they show that a reinforcement learning setup can lead to more informative summaries as opposed to usual classifier settings.

The model itself is a mix of a sentence encoder (using CNN’s), a document encoder (using LSTM’s) and a sentence extractor (again with LSTM’s). The sentence extractor chooses which sentence to select based on the sentence encoding, the document encoding, and the sentences selected so far.

Reinforcement Learning model for selecting sentences

The main novelty of the authors’ approach is the learning setup that they define. Rather than focusing on the cross-entropy loss to ensure that correct sentences are selected, they adapt the REINFORCE (more information on REINFORCE here) reinforcement learning algorithm to directly obtain sentences with higher ROGUE scores (average of ROGUE-1, ROGUE-2, and ROGUE-L).

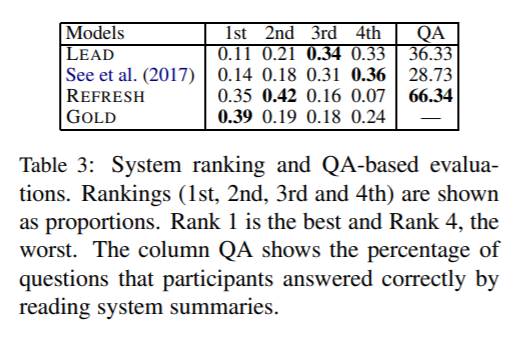

The datasets they used were the One Billion Word Benchmark one to pre-train word embeddings, and the CNN/DailyMail dataset to train the overall model. Their results show that in addition to the ROGUE (N=1, n=2, ROGUE-L) scores being comparable to models that don’t use RL, their model is more informative based on human evaluation. When they asked people to answer questions based on the summaries, people’s answers were the most accurate when using the authors’ model.

Results for RL Model

Despite these gains, it is worth noting that in order to properly train this algorithm, we would need a dataset that has a label for each sentence that states if the sentence is relevant to the summary or not. Furthermore, in its document encoder, they process the document backwards to ensure that the first sentences of the document are the ones with highest impact in the document encoding. This is based on the news article structure assumption, which might not hold for other sources.

Abstractive Methods

As mentioned in the introduction, abstractive methods aim to rephrase the source material in a shorter way. Given that we are no longer just selecting sentences from the original text, a lot of non-deep learning methods are no longer applicable. Furthermore, in order to train the models, the learning setup is often different from the classifier approach. Rather than identifying which sentences to select, often the aim is to learn a language model that can predict the next word based on the context and the previous words.

Attention-Based Methods

Attention models have been successfully used for datasets where there are long sequences and we want to capture information from all throughout the sequence (Cohan et al. 2018). One of the methods that has captured the attention (see what I did there?) of many is (Rush, Chopra, and Weston 2015) (repo here), with it being one of the first instances of effective neural-based summarization. In this paper, they set out to teach a model how to summarize individual sentences, i.e. how to rephrase and condense a sentence.

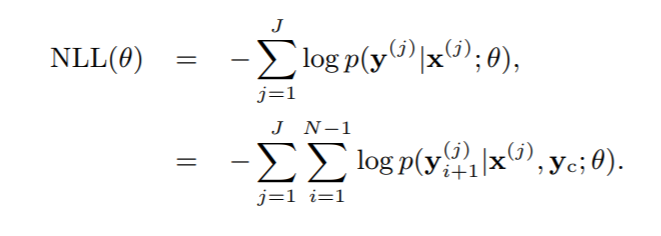

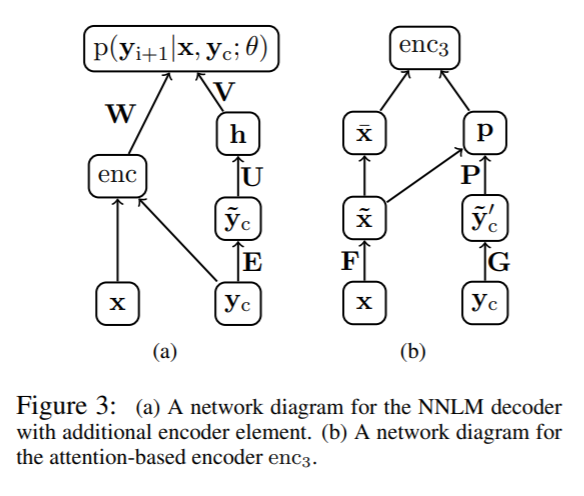

The model seeks out to maximize the probability of a word given the original text and the previous word (i.e. it wants to maximize the language model probabilities); consequently, during training they minimize the following negative log-likelihood equation:

where x are the words in the original sentence, y are the predicted words in the summary, and yc is the context vector (which often involves the words that have been previously predicted for the current sentence).

Regarding the architecture, they are using a standard encoder-decoder architecture. In the encoder part, they experiment with three different word encodings: bag-of-words, convolutional encoder, and an attention-based encoder. For the decoder, they experiment with two ways of generating word sequences: a greedy algorithm that samples the most likely word, and a beam search algorithm.

Attention model for abstractive summarization

The dataset that they use for training is the Gigaword dataset, and they evaluate their results on a heldout subset of the Gigaword dataset as well as the DUC-2004 dataset. The set up with these datasets has the first sentence of a news story as the input text, and the “target” summary is the title of the news story. To evaluate their results, they evalute the ROGUE-N (N=1, N=2) and ROGUE-L scores. They also show the perplexity of their generated results to check if these sentences “make sense”. All of their results show that their model outperforms all of their defined baselines (which are mostly models based on linguistics and statistics) in all metrics.

Despite the advances of this method, it is important to highlight some limitations. First, it is a sentence-to-sentence summarization rather than a document-to-paragraph one, which means you would likely end up with the same number of sentences as the original text. Along with this, the small length of the source material does not accurately reflect one of the main issues that comes up in summarization: having to identify important sentences/ideas. Finally, this method does not take into account the factual accuracy of the text.

Multi-Task/Multi-Reward

Given the flexibility of abstractive summarization and the multiple aspects that encompass good summarization, some methods employ more complex models that account for the multiplicity of the task. For instance, similar to the reinforcement learning in the extractive methods, (Kryściński et al. 2018) use a combination of RL and maximum likelihood to improve the ROGUE score directly. A more intricate model uses multiple tasks to achieve its goal of good summarization (Guo, Pasunuru, and Bansal 2018). This paper ensures that relevant information is present through an adaptation of the question answering field, and ensures text cohesion through sentence inference.

Given that the multi-task model has a larger scope, its model and setup are more intricate. The main idea of their approach is that they have trained a model to deal with three main tasks:

- a question generation task (to identify what are the main questions the summary ought to answer),

- an entailment generation task (understanding how two sentences are related to each other)

- a summary generation task

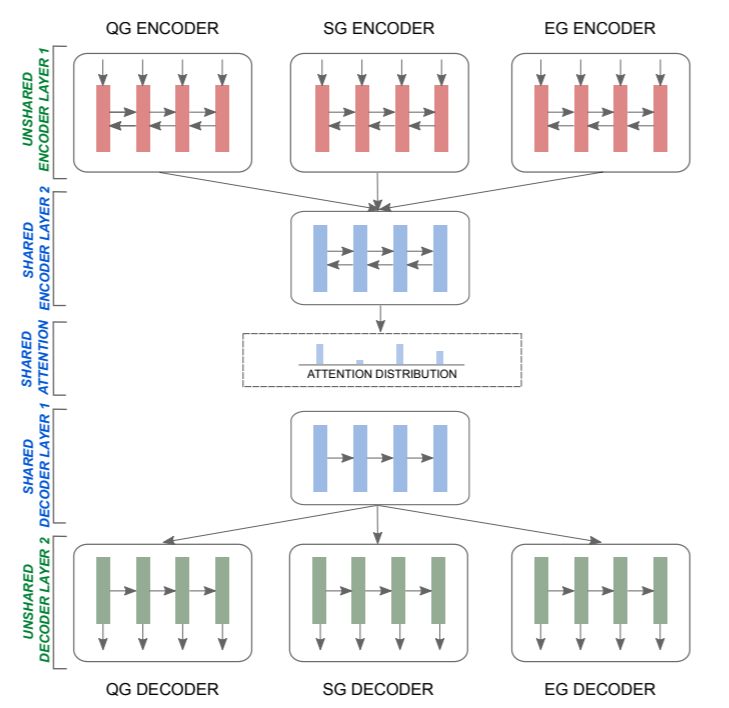

By having a model that uses mostly the same parameters for all three tasks, the network will have learned how to answer the correct questions and how to construct a summary that has coherent flow to it. The specifics of the model involve an encoder-decoder architecture that uses bidirectional LSTM’s for the encoder, LSTM’s for the decoder, a pointer-generator network (more on this here) for identifying words from the source document that are useful for the summary, and a coverage loss (more on this here) that helps avoid word repetitions.

Soft sharing scheme for multi-task summarization

where QG is the question generation network, SG is the summary generation one, and EG is the entailment generation one.

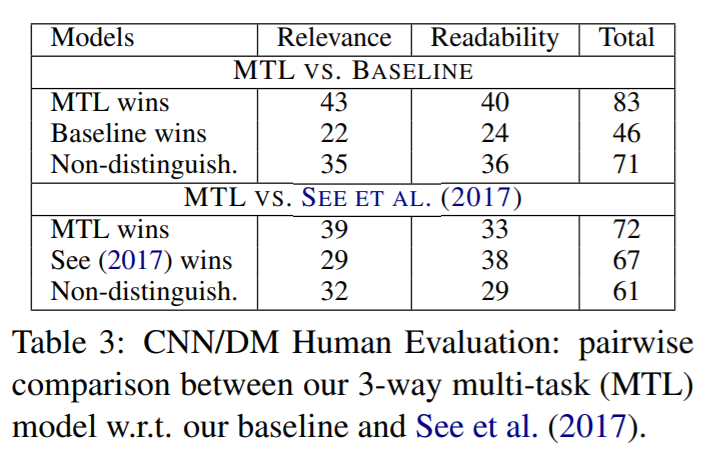

The dataset used for training are the CNN/DailyMail and Gigaword datasets for summarization, the Stanford Natural Language Inference dataset (more on this here) for the entailment generation, and the SQuAD dataset (more on this here) for the question generation tasks. Validation testing was done on the DUC-2002 and the CNN/DailyMail datasets. In addition to showing the ROGUE F1 (N=1, N=2, ROGUE-L) are better than their reported baselines and that the multi-task approach improves the baselines a bit, they show that humans tend to prefer the multi-task summaries over its non-multi-task counterpart.

Results for the Multi-task network

It is worth noting that despite the gains that are made through this multi-task approach, the difference between their approach with and without the multiple tasks is not that large. This raises the question of the tradeoff between model/training complexity and the performance gains from it.

Extractive and Abstractive Hybrid

In addition to purely extractive and abstractive methods, there has also been some work done in the intersection of these (Chen and Bansal 2018). The setup for these often involves using the extraction methods in order to select what sentence or paragraph is pertinent to the summary, and then using abstractive methods to compose a new text.

One paper that has gained traction in recent years is by scientists at Google Brain (Liu et al. 2018) (repo here). In this project, they aim to automatically generate Wikipedia summaries at the beginning of each article. The input for the model are the article’s reference sources and the Google search results when querying the article’s title, and the output is the generated summary of the article. By having an extractive phase followed by an abstractive one, they manage to train a model that is able to create decent Wikipedia summaries. What distinguishes this paper from others is its use of Wikipedia as a dataset as well as its mix of extractive and abstractive methods.

The first phase of the model is the extractive one, where they look at all paragraphs of all input documents and they rank them to assess how important is each paragraph. The methods that they test for extraction are all count-based, such as using tf-idf (more information on it here), bi-grams, word frequencies, and similarities.

Extractive model obtains relevant documents and paragraphs from those documents

After obtaining the ranking of the paragraphs, the abstractive part of the model uses these ordered paragraphs to generate the summary. To do so, they used a transformer architecture that does not use the encoder part, and they use the transformer architecture to predict the language model probabilities. They generate the words by using beam search of size 4 and a length penalty of 0.6, and they try to optimize for perplexity.

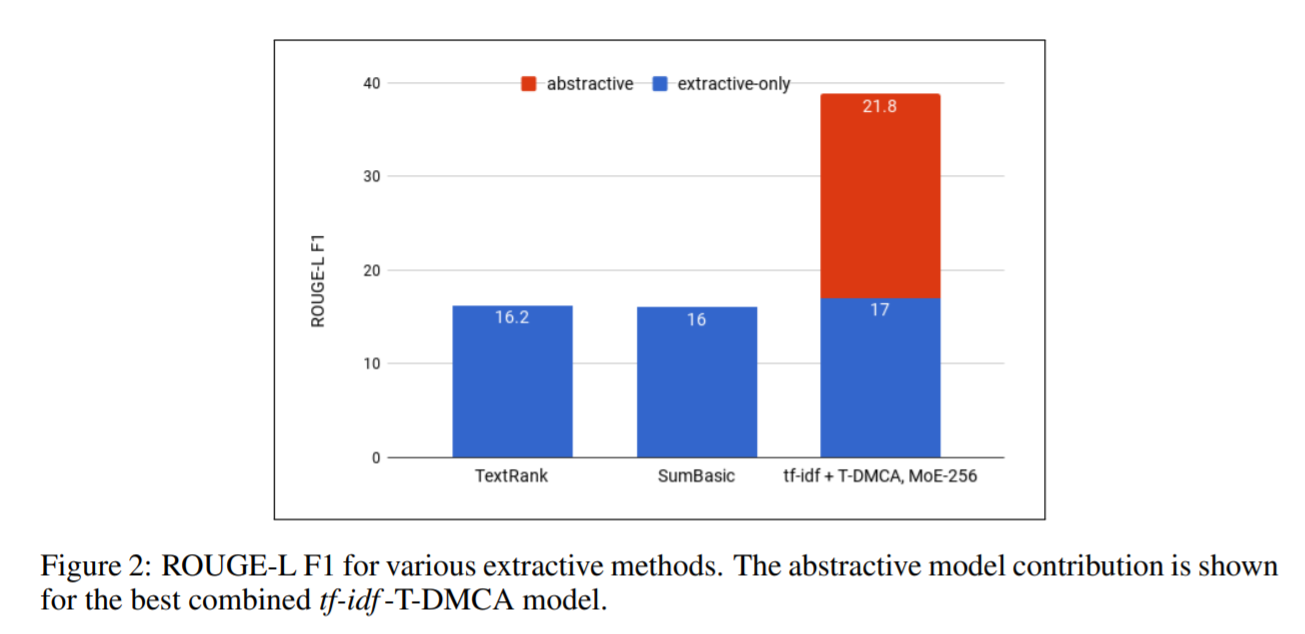

To evaluate their success, they used ROGUE-L F1, perplexity, and a qualitative human evaluation where they would state their preferences and evaluate the linguistic quality of the text. In addition to showing that their model performs quite well in the measures they list, they also show that the mix of the extractive and abstractive phases significantly improves the quality of the summaries.

Results for the extractive-abstractive model

where TextRank, SumBasic, and tf-idf are different extractive methods, and T-DMCA is the transformer architecture they used for the abstrative phase.

Closing Remarks

Automatic summarization is a field that has seen a lot of advances in recent years, with most of the deep learning advances occurring in the past four years. As the volume of data keeps increasing, demand for automatic summarization will increase as well. Furthermore, automatic summarization will play a key role in what kind of information most readers will see, since the sheer volume of documents and data will lead to a reliance on summaries.

Despite the advances shown in this summary about summarization, there is still a lot of room in this area for collaboration and growth. Furthermore, the space for research in this area spans all aspects of summarization from new models to new metrics, loss functions, problem setups, datasets, and validation techniques. We hope this blog post serves as a starting point for researchers, practitioners, and enthusiasts looking to know more about NLG and how to get started in this exciting and dynamic field.

References

- Allahyari, Mehdi, Seyedamin Pouriyeh, Mehdi Assefi, Saeid Safaei, Elizabeth D. Trippe, Juan B. Gutierrez, and Krys Kochut. “Text summarization techniques: a brief survey.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.02268 (2017).

- Brown, Peter F., Vincent J. Della Pietra, Robert L. Mercer, Stephen A. Della Pietra, and Jennifer C. Lai. “An estimate of an upper bound for the entropy of English.” Computational Linguistics 18, no. 1 (1992): 31-40.

- Cao, Ziqiang, Furu Wei, Wenjie Li, and Sujian Li. “Faithful to the original: Fact aware neural abstractive summarization.” In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2018.

- Chen, Yen-Chun, and Mohit Bansal. “Fast Abstractive Summarization with Reinforce-Selected Sentence Rewriting.” In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp. 675-686. 2018.

- Cohan, Arman, Franck Dernoncourt, Doo Soon Kim, Trung Bui, Seokhwan Kim, Walter Chang, and Nazli Goharian. “A Discourse-Aware Attention Model for Abstractive Summarization of Long Documents.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers), pp. 615-621. 2018.

- Goodrich, Ben, Vinay Rao, Peter J. Liu, and Mohammad Saleh. “Assessing the factual accuracy of generated text.” In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, pp. 166-175. ACM, 2019.

- Graff, David, Junbo Kong, Ke Chen, and Kazuaki Maeda. “English gigaword.” Linguistic Data Consortium, Philadelphia 4, no. 1 (2003): 34.

- Guo, Han, Ramakanth Pasunuru, and Mohit Bansal. “Soft Layer-Specific Multi-Task Summarization with Entailment and Question Generation.” In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp. 687-697. 2018.

- Hahn, Udo, and Inderjeet Mani. “The challenges of automatic summarization.” Computer 33, no. 11 (2000): 29-36.

- Hermann, Karl Moritz, Tomas Kocisky, Edward Grefenstette, Lasse Espeholt, Will Kay, Mustafa Suleyman, and Phil Blunsom. “Teaching machines to read and comprehend.” In Advances in neural information processing systems, pp. 1693-1701. 2015.

- Jing, Hongyan. “Using hidden Markov modeling to decompose human-written summaries.” Computational linguistics 28, no. 4 (2002): 527-543.

- Kryściński, Wojciech, Nitish Shirish Keskar, Bryan McCann, Caiming Xiong, and Richard Socher. “Neural Text Summarization: A Critical Evaluation.” In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), pp. 540-551. 2019.

- Kryściński, Wojciech, Romain Paulus, Caiming Xiong, and Richard Socher. “Improving Abstraction in Text Summarization.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 1808-1817. 2018.

- Lin, Chin-Yew. “Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries.” In Text summarization branches out, pp. 74-81. 2004.

- Liu, Peter J., Mohammad Saleh, Etienne Pot, Ben Goodrich, Ryan Sepassi, Lukasz Kaiser, and Noam Shazeer. “Generating wikipedia by summarizing long sequences.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.10198 (2018).

- Nallapati, Ramesh, Bowen Zhou, and Mingbo Ma. “Classify or select: Neural architectures for extractive document summarization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.04244 (2016).

- Napoles, Courtney, Matthew Gormley, and Benjamin Van Durme. “Annotated gigaword.” In Proceedings of the Joint Workshop on Automatic Knowledge Base Construction and Web-scale Knowledge Extraction, pp. 95-100. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2012.

- Narayan, Shashi, Shay B. Cohen, and Mirella Lapata. “Ranking Sentences for Extractive Summarization with Reinforcement Learning.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), pp. 1747-1759. 2018.

- Rush, Alexander M., Sumit Chopra, and Jason Weston. “A Neural Attention Model for Abstractive Sentence Summarization.” In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 379-389. 2015.

- ShafieiBavani, Elaheh, Mohammad Ebrahimi, Raymond Wong, and Fang Chen. “A Graph-theoretic Summary Evaluation for ROUGE.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 762-767. 2018.

- Yin, Wenpeng, and Yulong Pei. “Optimizing sentence modeling and selection for document summarization.” In Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2015.